Optimizing hybrid search in OpenSearch

Introduction

Hybrid search combines lexical and neural search to improve search relevance; this combination shows promising results across industries and in benchmarks.

In OpenSearch 2.18, hybrid search is an arithmetic combination of the lexical (match query) and neural (k-NN) search scores. It first normalizes the scores and then combines them with one of three techniques (arithmetic, harmonic, or geometric mean), each of which includes weighting parameters.

The search pipeline configuration is how OpenSearch users define score normalization, combination, and weighting.

Finding the right hybrid search configuration can be difficult

The primary question for a user of hybrid search in OpenSearch is how to choose the normalization and combination techniques and the weighting parameters for their application.

What is best depends strongly on the corpus, on user behavior, and on the application domain—there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

However, there is a systematic way to arrive at this ideal set of parameters. We call identifying the best set of parameters global hybrid search optimization: we identify the best parameter set for all incoming queries; it is “global” because it doesn’t depend on per-query factors. We will cover this approach first before moving on to a dynamic approach that takes into account per-query signals.

Global hybrid search optimizer

We treat hybrid search configuration as a parameter optimization problem. The parameters and combinations are:

- Two normalization techniques:

l2andmin_max. - Three combination techniques: arithmetic mean, harmonic mean, geometric mean.

- The lexical and neural search weights, which are values ranging from 0 to 1.

With this knowledge we can define a collection of parameter combinations to try out and compare. To follow this path we need three things:

- Query set: A collection of queries.

- Judgments: A collection of ratings that indicate the relevance of a result for a given query.

- Search quality metrics: A numeric expression indicating how well the search system performs in returning relevant documents for queries.

Query set

A query set is a collection of queries. Ideally, query sets contain a representative set of queries. “Representative” means that different query classes are included in this query set:

- Very frequent queries (head queries) but also queries that are rarely used (tail queries)

- Queries that are important to the business

- Queries that express different user intent classes (for example, searching for a product category, searching for product category + color, searching for a brand)

- Other classes, depending on the individual search application

These different queries are best sourced from a query log that captures all queries your users send to your system. One way of sampling these efficiently is Probability-Proportional-to-Size Sampling (PPTSS). This method can generate a frequency-weighted sample.

We will first run each query in the query set against a baseline to determine our search result quality at the beginning of this experimentation phase.

Judgments

Once a query set is available, judgments come next. A judgment describes how relevant a particular document is for a given query. A judgment consists of three parts: the query, the document, and a (typically) numerical rating.

Ratings can be binary (0 or 1, that is, irrelevant or relevant) or graded (for example, 0 to 3, definitely irrelevant to definitely relevant). In the case of explicit judgments, human raters review query-document pairs and assign these ratings. Implicit judgments, on the other hand, are derived from user behavior: user queries and viewed and clicked documents. Implicit judgments can be modeled with click models that emerged from web search in the early 2010s and range from simple click-through rates to more complex approaches. All come with limitations and/or deal differently with biases like position bias.

Recently, a third category of judgment generation has emerged: LLM-as-a-judge. Here a large language model like GPT-4o judges query-doc pairs.

All three categories have different strengths and weaknesses. Whichever you choose, you need to have a decent amount of judgments. Twice the depth of your default search result page per query is usually a good starting point for explicit judgments. So if you show your users 24 results per result page, you should rate the first 48 results for each query.

Implicit judgments have the advantage of scale: when already collecting user events (like queries, viewed documents, and clicked documents), this is an enabling step for calculating thousands of judgments by modeling these events as judgments.

Search metrics

With a query set and the corresponding judgments, we can calculate search quality metrics. Widely used search metrics are Precision, DCG, or NDCG.

Search metrics provide a way of measuring the search result quality of a search system numerically. We calculate search metrics for each configuration, and this enables us to compare them objectively against each other. As a result we know which configuration scored best.

If you’re looking for guidance and support in generating a query set, creating implicit judgments based on user behavior signals, or calculating metrics based on these signals, feel free to check out the search result quality evaluation framework.

Create a baseline with the ESCI dataset

Let’s put all the pieces together and calculate search metrics for one particular example: in the hybrid search optimizer repository we use the ESCI dataset, and in notebooks 1–3 we configure OpenSearch to run hybrid queries, index the products of the ESCI dataset, create a query set, and execute each of the queries in a lexical search setting that we assume to be our baseline. The search metrics can be calculated because the ESCI dataset comes not only with products and queries but also with judgments.

We chose a multi_match query of the type best_fields as our baseline. We search in the different dataset fields with “best guess” fields weights. In a real-world scenario we recommend techniques like learning to boost based on Bayesian optimization to figure out the best field and field weight combination.

{

"_source": {

"excludes": [

"title_embedding"

]

},

"query": {

"multi_match" : {

"type": "best_fields",

"fields": [

"product_id^100",

"product_bullet_point^3",

"product_color^2",

"product_brand^5",

"product_description",

"product_title^10"

],

"operator": "and",

"query": query[2]

}

}

}

To arrive at a query set, we used two random samples: a small one containing 250 queries and a large one containing 5,000 queries. Unfortunately, the ESCI dataset does not contain any information about the frequency of queries, which excludes frequency-weighted approaches like the above-mentioned PPTSS.

The following are the results of running the test set of both query sets independently.

| Metric | Baseline BM25 – Small | Baseline BM25 – Large |

|---|---|---|

| DCG@10 | 9.65 | 8.82 |

| NDCG@10 | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| Precision@10 | 0.27 | 0.24 |

We applied an 80/20 split on the query sets to arrange for a training and test dataset. Every optimization step uses the queries of the training set, whereas search metrics are calculated and compared for the test set. For the baseline, we calculated the metrics for only the test set because there is no actual training occurring.

These numbers are now the starting point for our optimization journey. We want to maximize these metrics and see how far we get when looking for the best global hybrid search configuration in the next step.

Identifying the best hybrid search configuration

With this starting point, we can explore the parameter space that hybrid search offers. Our global hybrid search optimization notebook tries out 66 parameter combinations for hybrid search with the following set:

- Normalization technique: [

l2,min_max] - Combination technique: [

arithmetic_mean,harmonic_mean,geometric_mean] - Lexical search weight: [

0.0,0.1,0.2,0.3,0.4,0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8,0.9,1.0] - Neural search weight: [

1.0,0.9,0.8,0.7,0.6,0.5,0.4,0.3,0.2,0.1,0.0]

Neural and lexical search weights always add up to 1.0, so we don’t need to choose them independently.

This leaves us with 66 combinations to test: 2 normalization techniques * 3 combination techniques * 11 lexical/neural search weight combinations.

For each of these combinations, we run the queries of the training set. To do so we use OpenSearch’s temporary search pipeline capability, making it unnecessary to pre-create all pipelines for the 66 parameter combinations.

Here is a template of the temporary search pipelines we use for our hybrid search queries:

"search_pipeline": {

"request_processors": [

{

"neural_query_enricher" : {

"description": "one of many search pipelines for experimentation",

"default_model_id": model_id,

"neural_field_default_id": {

"title_embeddings": model_id

}

}

}

],

"phase_results_processors": [

{

"normalization-processor": {

"normalization": {

"technique": norm

},

"combination": {

"technique": combi,

"parameters": {

"weights": [

lexicalness,

neuralness

]

}

}

}

}

]

}

norm is the variable for the normalization technique, combi is the variable for the combination technique, lexicalness is the lexical search weight, and neuralness is the neural search weight.

The neural part of the hybrid query searches in a field with embeddings that were created based on the title of a product with the model all-MiniLM-L6-v2:

{

"neural": {

"title_embedding": {

"query_text": query[2],

"k": 100

}

}

}

Using the queries of the training dataset and retrieving the results, we calculate the three search metrics DCG@10, NDCG@10, and Precision@10. For the small dataset, there is one pipeline configuration that scores best for all three metrics. The pipeline uses the l2 norm, arithmetic mean, a lexical search weight of 0.4, and a neural search weight of 0.6.

The following metrics are calculated:

- DCG: 9.99

- NDCG: 0.26

- Precision: 0.29

Applying the potentially best hybrid search parameter combination to the test set and calculating the metrics for these queries results in the following numbers.

| Metric | Baseline BM25 – Small | Global Hybrid Search Optimizer – Small | Baseline BM25 – Large | Global Hybrid Search Optimizer – Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCG@10 | 9.65 | 9.99 | 8.82 | 9.30 |

| NDCG@10 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| Precision@10 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.27 |

Improvements are seen across all metrics for both datasets. To recap, up to this point, we performed the following steps:

- Create a query set by randomly sampling.

- Generate judgments (to be precise, we only used the existing judgments of the ESCI dataset).

- Calculate search metrics for a baseline.

- Try out several hybrid search combinations.

- Compare search metrics.

Two things are important to note:

- While the systematic approach can be transferred to other applications, the experiment results cannot. It is necessary to always evaluate and experiment with your own data.

- The ESCI dataset does not provide 100% judgment coverage. On average we saw roughly 35% judgment coverage among the top 10 retrieved results per query. This leaves us with some uncertainty.

The improvements tell us that we optimize our metrics on average when switching to hybrid search with the above parameter values. But of course there are queries that benefit (as in their search quality metrics improve) and queries that do not benefit (as in their search quality metrics decrease) when conducting this switch. This is something we can virtually always observe when comparing two search configurations with each other. While one configuration outperforms the other on average, not every query will profit from the configuration.

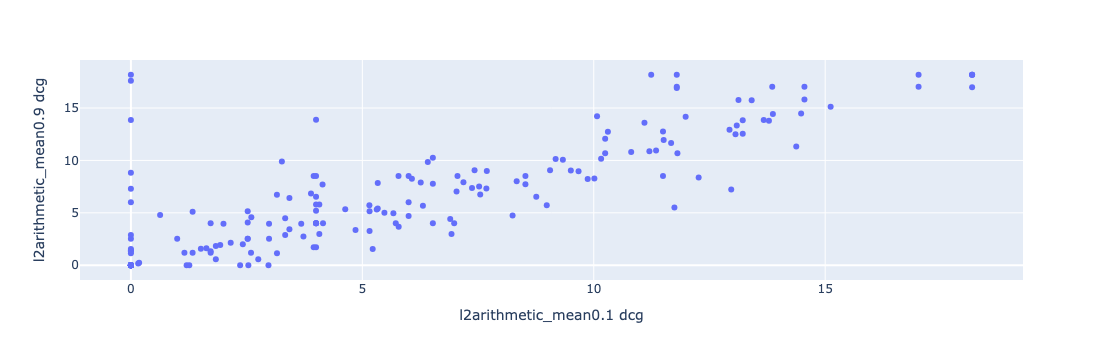

The following chart shows the DCG@10 values of the training queries of the small query set. The x-axis represents the search pipeline with l2 norm, arithmetic mean, 0.1 lexical search weight, and 0.9 neural search weight (configuration A). The y-axis represents the search pipeline with an identical normalization and combination technique but switched weights: 0.9 lexical search weight and 0.1 neural search weight (configuration B).

The queries with the highest search quality metric improvements of configuration B are those that are located on the y-axis: they have a DCG score of 0 for this configuration. And for configuration A some even score above 15.

Striving to improve the search quality metrics for all queries raises the following question: improvements on average are fine, but how can we tackle this in a more targeted way to come up with an approach that provides the best configuration per query instead of one good configuration for all queries?

Dynamic hybrid search optimizer

We call identifying a suitable configuration individually per hybrid search query dynamic hybrid search optimization. To move in that direction we treat hybrid search as a query understanding challenge: by understanding certain features of the query, we develop an approach to predict the “neuralness” of a query. “Neuralness” is used to describe the neural search weight for the hybrid search queries.

You may ask: Why predict only the “neuralness” and none of the other parameter values? The results of the global hybrid search optimizer (large query set) showed us that the majority of search configurations share two parameter values: the l2 normalization technique and the arithmetic mean as the combination technique.

Looking at the top 5 configurations per search metric (DCG@10, NDCG@10, and Precision@10), only 5 out of the 15 pipelines have min_max as an alternative normalization technique, and none of these configurations has another combination technique.

With this knowledge we assume the l2 normalization and the arithmetic mean combination technique to be best suited throughout the whole dataset.

That leaves us with the parameter values for the neural search weight and the lexical search weight. By predicting one we can calculate the other by subtracting the prediction from 1: by predicting the “neuralness” we can calculate the “lexicalness” by 1 - “neuralness”.

To validate our hypothesis, we created a couple of feature groups and features within these groups. Afterwards we trained machine learning models to predict an expected NDCG value for the given “neuralness” of a query.

Feature groups and features

We divide the features into three groups: query features, lexical search result features, and neural search result features:

- Query features: These features describe the user query string.

- Lexical search result features: These features describe the results that the user query retrieves when executed as a lexical search.

- Neural search result features: These features describe the results that the user query retrieves when executed as a neural search.

Query features

- Number of terms: How many terms does the user query have?

- Query length: How long is the user query (measured in characters)?

- Contains number: Does the query contain one or more numbers?

- Contains special character: Does the query contain one or more special characters (non-alphanumeric characters)?

Lexical search result features

- Number of results: The number of results for the lexical query.

- Maximum title score: The maximum score of the titles of the retrieved top 10 documents. The scores are BM25 scores calculated individually per result set. That means that the BM25 score is not calculated on the whole index but only on the retrieved subset for the query, making the scores more comparable to each other and less prone to outliers that could result from high IDF values for very rare query terms.

- Sum of title scores: The sum of the title scores of the top 10 documents, again calculated per result set. We use the sum of the scores (and no average value) as an aggregate to measure how relevant all retrieved top 10 titles are. BM25 scores are not normalized, so using the sum instead of the average seemed reasonable.

Neural search result features

- Maximum semantic score: The maximum semantic score of the retrieved top 10 documents. This is the score we receive for a neural query based on the query’s similarity to the title.

- Average semantic score: In contrast to BM25 scores, the semantic scores are normalized and in the range of 0 to 1. Using the average score seems more reasonable than attempting to calculate the sum.

Feature engineering

We used the output of the global hybrid search optimizer as training data. As part of this process, we ran every query 66 times: once per hybrid search configuration. For each query we calculated the search metrics, so we know which pipeline worked best per query and thus also which “neuralness” (neural search weight) worked best. We used the best NDCG@10 value per query as the metric to decide the ideal “neuralness.”

That leaves us with 250 queries (small query set) or 5,000 queries (large query set) together with their “neuralness” values for which they achieved the best NDCG@10 values. Next, we engineered the nine features for each query. This constitutes the training and test data.

Model training and evaluation findings

With the appropriate data at hand, we explored different algorithms and experimented with different model fitting settings to identify patterns and evaluate whether our approach was suitable.

We used two relatively simple algorithms: linear regression and random forest regression.

We applied cross-validation, regularization, and tried out all different feature combinations. This resulted in interesting findings that are summarized in the following section.

Dataset size matters: Working with the differently sized datasets revealed that the amount of data matters when training and evaluating the models. The larger dataset reported a smaller Root Mean Squared Error compared to the smaller dataset. The larger dataset also showed less variation of the RMSE scores within the cross-validation runs (that is, when comparing the RMSE scores within one cross-validation run for one feature combination).

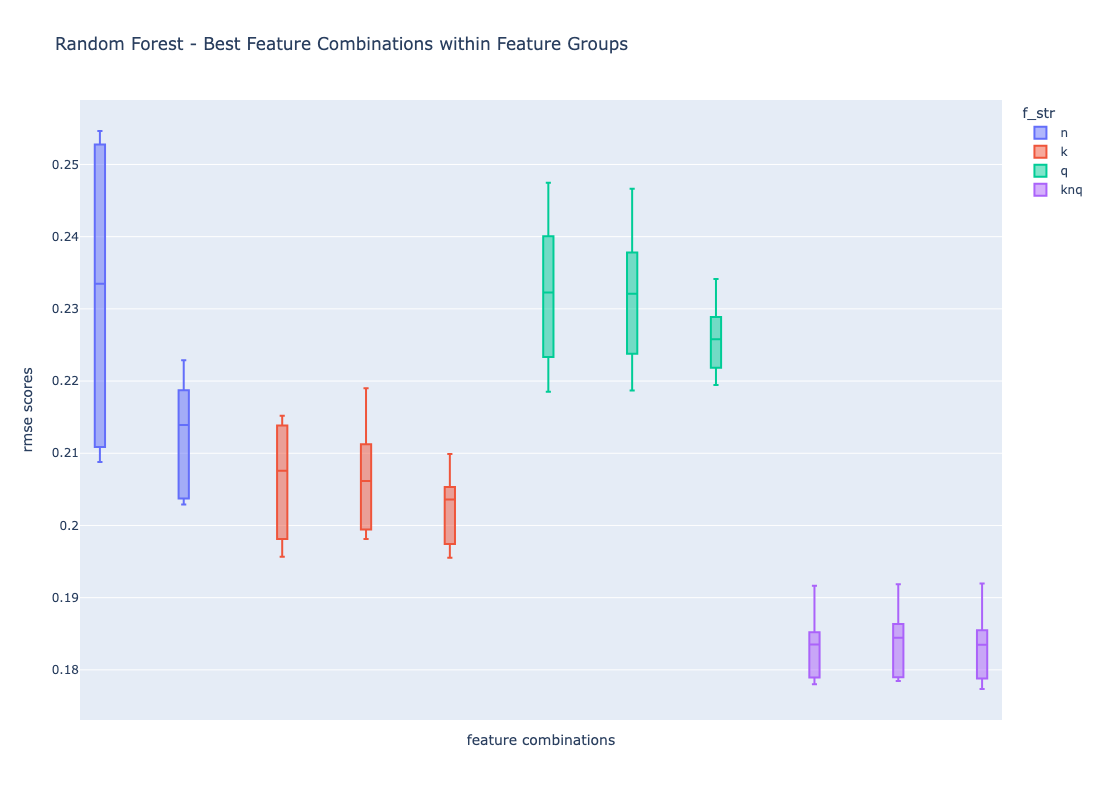

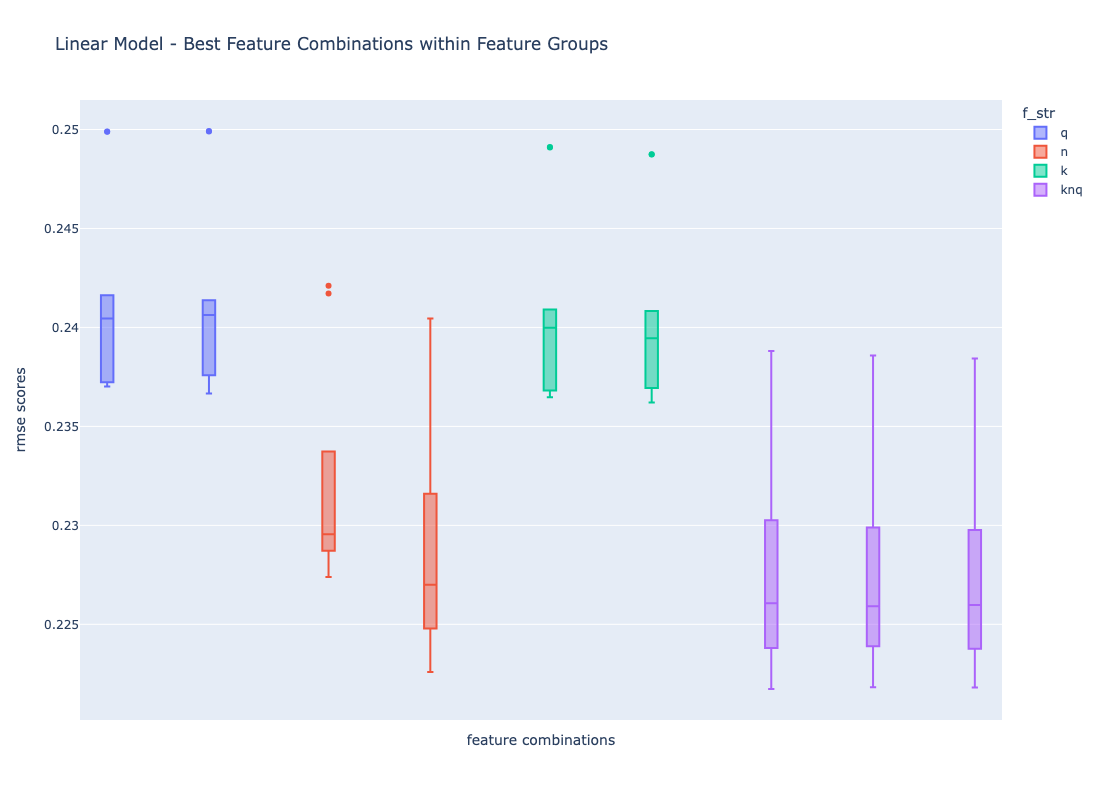

Model performance differs among the different algorithms: The best RMSE score for the random forest regressor was 0.18 compared to 0.22 for the best linear regression model (large dataset)—both with different feature combinations, though. The more complex model (random forest) performs better. However, better performance comes with the trade-off of longer training times for this more complex model.

Feature combinations of all groups have the lowest RMSE: The lowest error scores can be achieved when combining features from all three feature groups (query, lexical search result, and neural search result). Looking at RMSE scores for feature combinations within the feature groups shows that working with lexical search result feature combinations serves as the best alternative.

This is particularly interesting when thinking about productionizing this: putting an approach like this in production means that features need to be calculated per query during query time. Getting lexical search result features and neural search result features requires running these queries, which would add significant latency to the overall query even prior to inference time.

The following image shows the distribution of RMSE scores within one cross-validation run when fitting random forest regression models with feature combinations within one group (blue: neural search features, red: lexical result features, green: query features) and across the groups (purple: features from all groups). The feature mix (purple) scores lowest (best), followed by training on lexical search result features only (red).

The overall picture does not change when looking at the numbers for the linear model.

Model testing

Let’s look at how the trained models perform when applying them dynamically to our test set.

For each query of the test set we engineer the features and let the model make the inference for the “neuralness” values between 0.0 and 1.0 because “neuralness” is also a feature that we pass into the model. We then take the “neuralness” value that resulted in the highest prediction, which is the best NDCG value. By knowing the “neuralness” we can calculate the “lexicalness” by subtracting the “neuralness” from 1.

We again use the l2 norm and arithmetic mean as our hybrid search normalization and combination parameter values because they scored best in the global hybrid search optimizer experiment. With that, we build the hybrid query, execute it, retrieve the results, and calculate the search metrics like with the baseline and global hybrid search optimizer.

The following are the metrics for the small dataset.

| Metric | Baseline BM25 | Global Hybrid Search Optimizer | Dynamic Hybrid Search Optimizer – Linear Model | Dynamic Hybrid Search Optimizer – Random Forest Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCG@10 | 9.65 | 9.99 | 10.92 | 10.92 |

| NDCG@10 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| Precision@10 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.32 |

The following are the metrics for the large dataset.

| Metric | Baseline BM25 | Global Hybrid Search Optimizer | Dynamic Hybrid Search Optimizer – Linear Model | Dynamic Hybrid Search Optimizer – Random Forest Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCG@10 | 8.82 | 9.30 | 10.13 | 10.13 |

| NDCG@10 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| Precision@10 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

Looking at these numbers shows us a steady positive trend starting from the baseline and going all the way to the dynamic predictions of “lexicalness” and “neuralness” per query. The large dataset shows a DCG increase of 8.9%, rising from 9.3 to 10.13, and the small dataset shows an increase of 9.3%. The other metrics increase as well: NDCG shows an improvement of 7.4% for the large dataset and 10.3% for the small dataset, and Precision shows an improvement of 8% for the large dataset and 7.7% for the small dataset.

Interestingly, both models score exactly equally. The reason for this is that while they both predict different NDCG values, they predict the best ones with the same “neuralness” as an input feature. So while the models may differ in RMSE scores during the evaluation phase, they provide equal results when applied to the test set.

Despite the low judgement coverage, we see improvements for all metrics. This gives us confidence that this approach can provide value not only for search systems switching from lexical to hybrid search but also for those that are already are in production but have never used any systematic process to evaluate and identify the best settings.

Conclusion

We provide a systematic approach to optimizing hybrid search in OpenSearch based on its current state and capabilities (normalization and combination techniques). The results look promising, especially given the low judgment coverage provided by the ESCI dataset.

We encourage everyone to adopt the approach and explore its usefulness with their dataset. We look forward to hearing the community’s feedback on the provided approach on the OpenSearch forum.

Future work

The currently planned next steps include replicating the approach with a dataset that has higher judgment coverage and covers a different domain in order to determine its generalizability.

Optimizing hybrid search is not typically the first step in search result quality optimization. Optimizing lexical search results first is especially important because the lexical search query is part of the hybrid search query. Bayesian optimization is an efficient technique for efficiently identifying the best set of fields and field weights, sometimes also referred to as “learning to boost.”

The straightforward approach of trying out 66 different combinations can be performed more elegantly by applying a technique like Bayesian optimization as well. In particular, we expect this to result in a performance improvement for large search indexes and large numbers of queries.

Reciprocal rank fusion, currently under active development, is another way of combining lexical search and neural search:

- https://github.com/opensearch-project/neural-search/issues/865

- https://github.com/opensearch-project/neural-search/issues/659

We also plan to include this technique and to identify the best way of running hybrid search dynamically per query.